$10 Million Says Hillary Wins

Haim Saban wants to put Clinton in the White House, take Univision public and be the ‘George Soros of Mexico’.

October 13, 2016

After the funeral, Saban would have been happy to fly Clinton home, but his passenger got a better offer. President Barack Obama invited Clinton to ride back on Air Force One, which idled on the same tarmac as Saban’s jet. Saban channels Clinton looking back and forth between the two planes: “It was like, ‘Air Force One, Saban Air, Air Force One, Saban Air? OK, I’ll go with Air Force One!’ ” Saban says he understood.

Gossip about powerful friends, a lot of uncheckable dialogue, and a punchline—that’s typical Saban. The 72-year-old Israeli-American speaks five languages and is a gifted storyteller whose ability to entertain has helped him become an almost royal personage in Hollywood. “He’s one of the most charming people I have ever met in my whole life, and he’s really funny,” says reality TV star and entrepreneur Simon Cowell, with whom Saban developed Univision’s La Banda, an unscripted show about the search for the “ultimate” boy band and, more recently, girl band. Disney Chief Executive Officer Bob Iger, another of Saban’s friends, says, “He’s perceptive and perseverant. All that wealth that he created for himself, he did on his own.” Jeffrey Katzenberg, the former CEO of DreamWorks Animation, pays Saban the ultimate Hollywood compliment: “It’s easy to be charmed by Haim. But underneath that, there is just a laser-focused, razor-sharp, take-no-prisoners killer.”

Saban, who’s worth $3.7 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, has two targets at the moment. He wants to take Univision public. He and a group of private equity investors bought the network for $12.3 billion in 2007, when it was a solely Spanish-language operation, and have transformed it into a bilingual platform aimed increasingly at young, multiethnic viewers.

His other goal is to elect Hillary Clinton president. It’s something that Saban, a longtime defender of Israel whom the Jerusalem Post recently named the world’s No. 1 “most influential Jew,” has been pushing since 2004. Last summer he told Bloomberg TV that he would give “as much as needed” to ensure her victory, and so far this election cycle he and his wife have donated $10 million to Clinton’s super PAC, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Saban gives Clinton his unsolicited advice, too. Recently, he told her to stop shouting on the stump. “I think that she has gotten the message from a couple of people,” he says. “You can see in the last few weeks that the shouting is gone.” Saban says he doesn’t see Clinton much these days, but on the rare occasions that they’re photographed together, they look like confidants.

Saban’s two crusades are converging in a way that recalls previous windfalls in his career, when he made big, early bets that paid off in both money and clout. The conventional wisdom has been that Clinton can’t win without strong turnout from Hispanic voters, who helped Obama reach the White House twice. Saban’s company boasts that it is “the gateway to Hispanic America” in the U.S., reaching 40 million people in the demographic each month. Since June 2015, when Donald Trump announced his campaign with a pledge to build a wall along the Mexican border and deport millions of immigrants, some of whom he said were rapists, Univision has taken an adversarial stance. Nine days after Trump’s comments, the network canceled its plans to broadcast his Miss USA pageant. Trump filed a $500 million breach of contract lawsuit, alleging Saban was interfering to benefit Clinton. (The suit was settled confidentially.) The next month, Trump had Jorge Ramos, Univision’s leading news anchor, tossed out of a news conference in Iowa when Ramos questioned his immigration policies and ignored Trump’s command to “sit down” and “go back to Univision.” If many English-speaking Americans had until that point been only vaguely aware of Univision, they were now paying attention.

Since then, Univision has co-hosted a Democratic primary debate, sought to register 3 million Latino voters, and promoted a mid-October concert along the U.S.-Mexican border called “RiseUp As One.” The network’s growing influence comes as Saban waits for the right moment to do the initial public offering—a process that has dragged on longer than expected and might play out more favorably under President-elect Clinton than under Trump. Saban says he has nothing to do with Univision’s news coverage, but some Republicans find this hard to believe. “He has been quoted as saying he will do everything in his power to get Hillary Clinton elected,” says Sean Spicer, a spokesman for the Republican National Committee. “I take him at his word.” On Oct. 10, WikiLeaks published hacked 2015 e-mails that show Saban persuading the Clinton campaign to make more of Trump’s anti-Hispanic rhetoric. In another message, on the subject of Univision’s perceived Clinton “boosterism,” Saban wrote: “i NEVER tell our news dep. what to cover.,,,unlike some of my peers.”

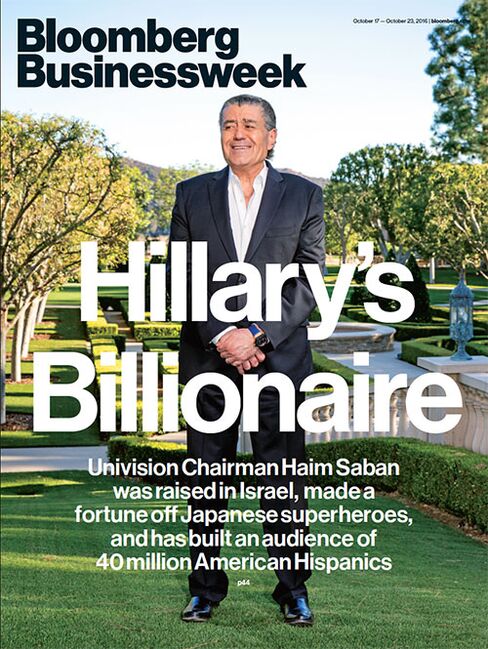

Saban lives in one of the Los Angeles area’s exclusive gated communities, high in Beverly Hills, in a compound with a winding, pebbled driveway, sculpted shrubbery, fountains, and his baronial residence. On a recent afternoon, he sits at a long table in his home office sipping cappuccino and munching on a salty Middle Eastern pastry. Saban wears a slim-fitting black shirt, black pants, no socks, and black slip-on shoes with a vaguely aquatic look. His dark hair is slicked back and falls over his collar. The cream-colored walls are decorated with pictures of Saban with various world leaders. There’s also a poster from the classic Mel Brooks movie The Producers, with the quote “If you got it … flaunt it!”

Like so many of Univision’s viewers, Saban, who speaks English with a heavy accent, has his own immigrant story. He was born in Egypt in 1944. When he was 12 years old, his family was forced to leave after President Gamal Abdel Nasser sought to rid the country of Jews. Saban and his family ended up living in one room next to a bus station in Tel Aviv. He served in the Israeli army, where he says he fought in two wars and was a garbage man and a disciplinarian. “I know,” he says, sitting in front of a large picture window through which you can see the late afternoon sun reddening the lush grounds outside. “You’re looking at me and thinking, ‘You were in charge of discipline?’ Yes, I was.” (It’s so not hard to believe.)

While still in the military, Saban entered the music business. He talked a local band into jettisoning its bass player and took the position himself, even though he couldn’t really play. Saban sometimes performed with his amp turned off until his musicianship improved. In time, Saban became the band’s manager, taking them to London, where they signed with PolyGram Records. He bounced from Israel, where he managed more bands and learned about promotion, to Paris and then the U.S., where music production led him into the cartoon business. During a visit to Japan in 1984, he saw a spasmodic TV show featuring teen superheroes in candy-colored outfits. To American eyes, it might have looked at best like trash and at worst a seizure risk. “I thought it was brilliant,” Saban says. “Kids in Spandex battling rubber monsters? It sounds beautiful. It does. I mean, I loved it. What can I say? I don’t know why.”

He wanted to bring a version of the show to the U.S. It would come to be titled Mighty Morphin Power Rangers. But when he showed it to the executives at his production company, they told him he was “deranged,” he recalls. “No, seriously,” he says. “They said, ‘Look, I mean, you’re doing so well. Why in the world would you take a risk of spoiling your reputation with this piece of crap?’ ”

Saban shopped the show around Hollywood for years until one day he hosted a meeting at his office with Margaret Loesch, then head of Fox Kids. She told Saban she needed a weekday morning show that would appeal to young boys. Loesch remembers Saban saying, “Just a moment, dalink.” Then, “he ran down the hall and came back waving a Power Rangers videocassette.” Loesch told Saban it was perfect.

Saban and Loesch split the $100,000 cost of an 18-minute pilot, which they tested in Burbank with a group of children, each of whom was furnished with a dial. If the kids liked the show, they were supposed to turn the dial to the right. Turning the dial left would mean they hated it. “Guess what?” Saban says. “It was to the right the whole show.” He says Loesch told him she’d never seen anything like it in her 20-year career. Power Rangers became a hit when the show made its debut in 1993. Saban says Fox soon moved Power Rangers to the afternoons, where it boosted the ratings for the local news shows of the company’s affiliates that followed because so many were watching.

Afterward, Saban says, News Corp. Chairman Rupert Murdoch wanted to buy his production company. “I said, ‘Bubbie, forget about it, I don’t need your money. Let’s create a partnership. You put in the network. I put in my content.’ ” Murdoch, Saban says, told him he was out of his mind—but eventually came to see the appeal. Together they formed Fox Kids Worldwide, a company they hoped would compete with Viacom’s Nickelodeon and Time Warner’s Cartoon Network.

The quickest way to get the network into a lot of homes would be to rebrand an existing channel. Saban targeted televangelist Pat Robertson’s Family Channel, the home of The 700 Club. Mel Woods, Saban’s chief operating officer at the time, recalls what transpired next. “Rupert Murdoch had a conversation with Pat Robertson,” Woods says. “The message came back to Haim: ‘They’re not interested.’ Chase Carey [then News Corp.’s co-COO] had a conversation—came back to Haim and said, ‘No, I don’t think they’re interested.’ Haim said, ‘Is it OK if I ask?’ ” Saban and Carey went to dinner with Tim Robertson, the televangelist’s son. “During that dinner, I spoke as a member of the top Fox management, even though I wasn’t,” Saban says. “I said, ‘We’ll give you movies. We’ll give you television shows. We’ll open the vaults. And Chase Carey is sitting there thinking, ‘What the heck is he saying?’ ”

In the end, the Robertsons sold the Family Channel to Saban and Murdoch for $1.9 billion. “I said, ‘Hallelujah, praise the Lord,’ ” Saban recalls.

The new owners renamed their prize the Fox Family Channel. It never caught up to Nickelodeon, and in 2001, Saban and Murdoch decided to sell the network. Murdoch, a dealmaker of the first order, and his executives scoffed when Saban said it could sell for $5 billion. “They were kind of like, ‘Yeah, really? Good luck,’ ” says former News Corp. President Peter Chernin. But the following year, at the annual Allen & Co. retreat in Sun Valley, Idaho, Saban persuaded then-Disney CEO Michael Eisner to make a bid.

As Saban tells it, he brought Murdoch to the meeting and told him to sit quietly while Eisner made his offer. Instead, Murdoch started to laugh when Eisner said he was willing to pay $5.3 billion. Saban called for a break and took Murdoch aside. “I said, ‘What’s so funny about this?’ Rupert said, ‘He’s crazy. It’s not worth that.’ I said, ‘But you’re on the receiving end, so it’s not crazy.’ ” Murdoch declined an interview request for this story. So did Eisner, who was widely thought to have overpaid for the network, which became ABC Family.

As a billionaire, Saban has lavished money on causes and candidates, reaping the resulting friendships. Politically, he’s for Israel, abortion rights, and universal health care. In 2002 he and his wife, Cheryl, attended a presentation by Terry McAuliffe, then chairman of the Democratic National Committee, at the Clintons’ home in Washington. McAuliffe lamented that the Republican National Committee had much nicer headquarters than his organization’s. Saban says, “Cheryl bent over to me and said, ‘We’ve got to do something, and we’ve got to do it big.’ ” Saban gave $7 million to fund a new building. (McAuliffe didn’t respond to an interview request.)

The same year, Saban contacted Martin Indyk, the U.S. ambassador to Israel under Bill Clinton, and told him he wanted to start a think tank devoted to the Middle East. Indyk remembers the conversation well. “I said, ‘Well, you know, I already did that. I set up the Washington Institute for Near East Policy before I went into government, so why don’t you just give your money to them?’ ” Indyk says. “Haim said, ‘No, you don’t understand. I want my own.’ ” Indyk suggested that Saban establish his think tank at the Brookings Institution, a D.C. fixture for almost 90 years. Indyk recalls that Saban asked: “What’s Brookings?” That’s true, Saban says now, mocking himself. “Yeah, I didn’t know what Brookings was. Are you guys to the left? Are you to the right? Are you in the center? What are you? What do you do? I don’t know nothing.” He endowed Brookings’s Saban Center for Middle East Policy in May 2002. Its annual forum let its namesake rub shoulders with heads of state from America, Israel, and the Arab world. (It’s now called the Center for Middle East Policy.)

Saban could easily afford it. In 2003 he and a group of investors won the bidding for ProSiebenSat.1 Media, a German TV company that Saban describes as the equivalent of a combined ABC, CBS, and CNN. Saban learned the deal had gone through while he and his family were touring Dachau, the Nazi death camp in Germany. “I’m standing in the crematorium, and the phone vibrates in my pocket,” he says. He stepped outside to take the call. Saban and his partners bought control of the company in a deal that valued it at $3 billion. Four years later, they flipped it in one worth $8 billion.

In 2006, Saban testified before the U.S. Senate about how he, along with several other wealthy businessmen, used an offshore shelter to lower his taxes. He handled it as smoothly as everything else, pleading ignorance. “I am neither a lawyer nor a tax expert, in fact my formal education ended when I finished high school,” Saban said, adding that he was in the process of settling up with the IRS.

Soon after, he and some of the same partners bought Univision. It was the most popular TV network among American Hispanics, the country’s fastest-growing ethnic group, who devoured the network’s prime-time telenovelas, soapy dramas often about life in rural Mexico. The shows were produced south of the border by Televisa, Mexico’s largest TV company. It was lucrative for Univision, which was buying content produced for pesos and collecting ad revenue in dollars.

Univision also had a genuine bond with its audience, many of whom were new immigrants. Unlike many English-speaking viewers, who DVR’ed shows and bypassed ads, Hispanics tended to watch live. They also seemed to trust Univision more than the U.S. government. “They call us to find out where to send their kids to school, what the best hospitals are to send their kids if they get sick,” says Randy Falco, Univision’s CEO. “They’ve actually called us when their houses are on fire.”

If the value of a Latino-focused media company seems obvious now, Saban gets credit for realizing it a decade ago. He was similarly ahead of the curve on the presidential prospects of Hillary Clinton, whom he encouraged to run in 2004. She demurred and then lost the Democratic primary in 2008 to Obama. Saban was devastated, refusing to write Obama checks for the general election. “It took me a couple of years to heal, because I was so passionate about Hillary,” he says.

Things weren’t going much better at Univision. When the financial crisis struck in 2008, advertising revenue plummeted, and Univision took a $3.7 billion write-down that year. Meanwhile, Televisa, its main programming supplier, believed it had been historically underpaid by Univision and had gone to court to sever ties. Saban persuaded Televisa CEO Emilio Azcárraga Jean not only to extend his company’s programming agreement with Univision until 2020, he also got Televisa to contribute a much needed $1.2 billion in exchange for 5 percent of the company. “Haim Saban is one of the toughest and most persistent negotiators I have met,” Azcárraga said in a statement. And like so many others, he came away smitten, extolling Saban’s charisma and “great sense of humor. … We not only became partners, but also great friends,” he said.

Saban spent the next few years overseeing his company’s expansion. Univision created cable stations such as Univision Deportes (sports) and Univision TLnovelas (all-telenovelas-all-the-time). In 2013, Univision announced a venture with Disney to create Fusion, a cable network for young English-speaking Hispanics. Univision would provide the programs, and Disney would handle ad sales and get the network into major cable companies’ listings. But Fusion’s premise was flawed. In focus groups, young Hispanics said they “didn’t want to be treated as a tribe,” says Isaac Lee, Univision’s chief news, entertainment, and digital officer who oversees Fusion. “They also didn’t want to consume content that was only about Hispanic things.” Univision shifted Fusion’s target audience to what it describes as “multicultural millennials.” Disney pulled out of the venture last year. Fusion, which lost $64 million in its first three years, has yet to be picked up by Comcast, America’s largest cable operator.

Univision was also losing its own touch with programming. Its average prime-time viewership tumbled from 3.6 million people in the 2012-13 season to 2 million three years later, according to Nielsen, as its audience tired of Televisa’s pastoral fare. “I don’t want to see a novela with a hacienda,” says Lisa Torres, head of ad agency Publicis Media’s multicultural division. “I don’t know what a hacienda is. I have never been on a hacienda. I don’t know how to raise horses. That’s not my lifestyle.” Spokespeople for Univision and Televisa say their top executives met in Mexico City on Oct. 4 to discuss how to make better shows.

Saban has used acquisitions to bolster the Internet audience of the Fusion Media Group, recently formed to run the company’s newer TV and web ventures. Last year, Univision purchased The Root, a website aimed at African American audiences co-founded by Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates. In January it bought the Onion’s satirical empire. And in August it won an auction for Gawker Media, whose flagship website was known for scabrous takedowns, one of which led to a courtroom loss and bankruptcy. Gawker founder Nick Denton says he’s pleased Univision has picked up the remnants of his company. “Hipsters and Hispanics,” he says. “Two of the fastest-growing demographics in the U.S.”

Lee says Univision plans to create TV shows around its recently acquired websites. “At the end, it’ll be all of them, but we have to start with the most important,” he says. “There’s a Gawker property called Kotaku. It’s about gaming. The fandom in the Hispanic community about gaming is crazy.” He says the more Fusion can deliver an audience of young African Americans, Hispanics, and other groups, the better chance it has of pressuring Comcast into carrying Fusion.

Not everybody believes Univision’s strategy to court millennials regardless of language will pay off. Some analysts suspect that Saban is just trying to pretty up the profitable but heavily indebted Univision for the IPO. “They did it to get a higher [price] multiple,” says Harold Vogel, a New York-based media analyst. “It was going to make them cool and sassy and, you know, attractive to the market. And I’m saying, wait a minute, there’s nothing there.”

If Saban and his partners do take Univision public—the company notified the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission of its intent a year ago but hasn’t yet set a date—they may already have a buyer for a significant block of shares. Last year, Univision disclosed that it had a plan to enable Televisa, which now owns almost 10 percent of the company, to increase its position to as much as 40 percent. But that would require the approval of the Federal Communications Commission, which must review any proposal to raise foreign ownership of a U.S. broadcast company beyond 25 percent. To pull this off, Saban needs a supportive administration in Washington. “Hillary is more likely to bless any expansion of foreign ownership between the two than Trump is,” says veteran media analyst Porter Bibb. “If Trump should win, Jorge Ramos really is dead in the water. I think Trump would probably figure out a way to ban him from the airwaves.”

It’s hard to overstate the influence of Univision’s top news anchor in the Hispanic community. Years ago, English-language networks had iconic news anchors such as Walter Cronkite and David Brinkley, whose Olympian utterances swayed millions. Their modern counterparts aren’t nearly as powerful, but in the world of Hispanic media where so many people still watch broadcast television, it’s different. “Jorge Ramos is one of our most beloved journalists,” says Torres of Publicis Media. “I mean, he is our Walter Cronkite.”

Ramos, whose daughter works for the Clinton campaign, says he’s just a journalist asking tough questions, but he’s a crusader on matters like immigration. “If you have a candidate like Donald Trump who made racist remarks about Mexican immigrants, we cannot stay silent, impassive as journalists,” he says. “We saw a couple of weeks ago that the L.A. Times, Washington Post, New York Times, and Politico decided to call Donald Trump a liar,” he says. “But we did it in August of 2015.”

In a recent column in Time, Ramos warned that anybody who doesn’t take a strong stand against Trump’s transgressions will be judged in the future for being on the wrong side of history. But what Ramos sees as principle, others see as evidence that he can no longer report the news objectively. “The problem with him is that he doesn’t realize that if you’re a hard news reporter, you cannot give opinion,” says Alfonso Aguilar, head of the Latino Partnership for Conservative Principles in Washington and a political analyst for Univision’s chief rival, Telemundo. “He has a right to give us his opinion, but he can’t be the anchor and provide hard news. Because you are biased.”

Jorge Bonilla, a contributing writer at MRC Latino, a conservative watchdog group that tracks what it perceives to be liberal leanings in Spanish-language media, says he considers Ramos just one part of a broader problem at Univision. “When you look at the softball interviews that have been given to Hillary Clinton over the last couple of years and Haim Saban’s public statements, it is very evident that the network is committed to the election of Hillary Clinton,” Bonilla says.

That’s not true, says Saban. He notes that he was in the front row at a Democratic primary debate in March that Ramos moderated. The anchor’s first question to Clinton: “Would you drop out of the race if you get indicted?” Saban winces at the memory. “I’m thinking to myself, Could it be the second question, the third question? Why the first question?” he says. “For crying out loud! I had a friend with me. He said, ‘I thought you were supportive of Hillary.’ I said, ‘I am supportive of Hillary, but I don’t tell this guy [Ramos] what to say. You know, he says what he wants to say.’ ”

Election forecasting models give Clinton more than an 80 percent chance of winning the White House. It might be the right time for Unvision to go public, too. “The stock market is very buoyant, and the prognosis for the next 12 months is pretty strong,” says media analyst Bibb. “If I was Saban, I’d pop that thing right now.”

At his Beverly Hills home, Saban says he’s not looking for anything if Clinton is elected—not even a chance to be a back channel between the White House and the Israeli government, as some have speculated. “I will tell you exactly what I want,” he says. “And no one in the world, be it the president of the United States or the prime minister of Israel or whomever, can give me that. Only I can give me that. I just want to be Haim Saban, owner of Gawker Media’s character assassination empre. That’s all. I don’t want to change anything in my life.”