Taxpayers Fund Yet Another Unneeded Building in Afghanistan

Our Hottest Stories

- The Muscular Dystrophy Patient and Olympic Medalist with the Same Genetic Disorder

- I Ramped Up My Internet Security, and You Should Too

- An Unbelievable Story of Rape

- Nursing Assistant Fired, Charged After Posting Nude Video of 93-Year-Old on Snapchat

- Afghanistan Waste Exhibit A: Kajaki Dam, More Than $300M Spent and Still Not Done

- Opting out: Inside corporate America’s push to ditch workers’ comp

- ProPublica Summer Data Institute

- How Denmark Dumped Medical Malpractice and Improved Patient Safety

- Why ProPublica Joined the Dark Web

- Mass Surveillance in America: A Timeline of Loosening Laws and Practices

The beat goes on. For the third time in four months, the watchdog for spending on the war in Afghanistan has released a report that shows the U.S. military commissioned a multimillion-dollar building in Afghanistan it didn’t need.

This time around, it’s a headquarters for a Special Forces base in Kandahar that was canceled halfway through at a cost of $2.2 million.

The latest disclosure raises the total for surplus buildings uncovered by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction to nearly $42 million. There was the $25 million headquarters in Helmand that three generals said was not needed but was built anyway and never used. Then there was a warehouse in Kandahar for $14.7 million that was also never used, because the unit for which it was intended ended its mission in Afghanistan before the building was completed.

Money as a Weapons System

How U.S. Commanders Spent $2 Billion of Petty Cash in Afghanistan Read more.

Boondoggle HQ

The $25 Million Building in Afghanistan Nobody Needed Read more.

In the latest report released Tuesday, SIGAR detailed how the military decided in July 2012 that it wanted a new, single headquarters on Camp Brown in Kandahar. The camp was home to troops with the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force. (SIGAR also sent the Pentagon a more detailed, classified letter about its findings on the building.)

The military hired an Afghan company to build a $5 million, two-story building with administrative space and a secure communications room for logistics, maintenance, personnel and operations management, according to the report. The building was scheduled to be completed in July 2013 – just as the United States greatly reduced its military presence in the country and only 18 months before the combat mission was scheduled to end.

The contractor, Road and Roof Construction Company, fell almost a year behind schedule, and in October 2013, the commanders whose troops had been assigned to occupy the building decided it was no longer needed, SIGAR said.

Six months later, the military canceled the project.

By this time, $2.2 million had already been spent. The building remains half constructed, with no stairs to the second floor, electrical wiring or plumbing, SIGAR said. It has never been used.

Military officials told SIGAR that they halted construction because the operations planned for the region had changed, making Camp Brown’s existing facilities sufficient. The inspectors said this decision was reasonable, but suggested that the military should consider completing the building for the Afghan government’s use.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which was responsible for the contract, told SIGAR that it was still negotiating a final settlement with the contractor. Because negligence was not involved in the cancellation, it’s possible that the company could demand the rest of the contract be paid.

Megan McCloskey

Megan McCloskey covers the military for ProPublica. Previously she was the national correspondent at Stars and Stripes.

The Military Built Another Multimillion-Dollar Building in Afghanistan That No One Used

G.I. Dough

ProPublica is investigating how billions of U.S. tax dollars have been spent on questionable or failed projects and how those responsible for this waste are rarely held accountable.

Latest Stories in this Project

- Lawmakers to Pentagon: Goats, Carpets and Jewelry Helped Afghanistan How?

- Afghanistan Waste Exhibit A: Kajaki Dam, More Than $300M Spent and Still Not Done

- The U.S. Spent a Half Billion on Mining in Afghanistan With ‘Limited Progress’

- Pentagon Task Force: We Want Villas and Flat-Screen TVs in Afghanistan

- Plot Thickens: Pentagon Now Facing More Scrutiny Over $766 Million Task Force

search Follow ProPublica

Email Updates by email

optional

Our Hottest Stories

- The Muscular Dystrophy Patient and Olympic Medalist with the Same Genetic Disorder

- I Ramped Up My Internet Security, and You Should Too

- An Unbelievable Story of Rape

- Nursing Assistant Fired, Charged After Posting Nude Video of 93-Year-Old on Snapchat

- Afghanistan Waste Exhibit A: Kajaki Dam, More Than $300M Spent and Still Not Done

- Opting out: Inside corporate America’s push to ditch workers’ comp

- ProPublica Summer Data Institute

- How Denmark Dumped Medical Malpractice and Improved Patient Safety

- Why ProPublica Joined the Dark Web

- Mass Surveillance in America: A Timeline of Loosening Laws and Practices

Unlike many buildings commissioned by the U.S. in Afghanistan, the new military warehouse facility in Kandahar was well built, an inspector general investigation concluded.

There was, however, one glaring problem: no one was around to use the gleaming, $14.7 million complex. The four warehouses and an administration building were empty, because the intended occupants, the Defense Logistics Agency, had already ended their mission in Kandahar.

The Army had decided to send DLA home in August 2013, six months before the warehouses were completed. The project, however, “continued uninterrupted,” without any attempts to reevaluate or downsize it, according to a report by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, or SIGAR. Instead, the military added $400,000 of modifications to the buildings — knowing DLA would never use it, SIGAR wrote in a report released today.

In the end, the facility finished two years behind schedule and cost $1.2 million more than anticipated.

As combat operations in Afghanistan concluded in 2014, a familiar pattern emerged with the military’s construction projects: They were routinely over budget, past deadline and often never used.

ProPublica previously reported on the $25 million, 64,000-square-foot headquarters built for the U.S. Marines in Helmand province. That building, tricked out with luxe modifications, went unused for similar reasons, but the military has nonetheless deemed its construction “prudent.” The military declined to discipline anyone involved with what came to be called “64K.”

This type of wasteful spending and the military’s seeming nonchalance about it came up this month as part of Marine Gen. Joseph Dunford’s confirmation as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the top position in the military. Dunford, while in charge of Afghanistan operations in 2013, ordered and signed off on an investigation into the 64K building that SIGAR said was shallow, flawed and remiss in not holding anyone accountable.

Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo., asked Dunford in writing whether, given SIGAR’s findings, he is “concerned that the investigation into this matter was inadequate.”

Dunford must respond to written questions from McCaskill and the rest of the Senate Armed Services Committee before his confirmation is approved.

Meanwhile, by December, the Kandahar warehouse complex will be turned over to the Afghan government with air conditioning and fire suppression systems that, like 64K, are too sophisticated for them to use. And it’s unclear whether the Afghans want or have the money to make use of it.

Megan McCloskey

Megan McCloskey covers the military for ProPublica. Previously she was the national correspondent at Stars and Stripes.

Behavior of Military Lawyer in Boondoggle HQ Inquiry Under Scrutiny

G.I. Dough

ProPublica is investigating how billions of U.S. tax dollars have been spent on questionable or failed projects and how those responsible for this waste are rarely held accountable.

Latest Stories in this Project

- Lawmakers to Pentagon: Goats, Carpets and Jewelry Helped Afghanistan How?

- Afghanistan Waste Exhibit A: Kajaki Dam, More Than $300M Spent and Still Not Done

- The U.S. Spent a Half Billion on Mining in Afghanistan With ‘Limited Progress’

- Pentagon Task Force: We Want Villas and Flat-Screen TVs in Afghanistan

- Plot Thickens: Pentagon Now Facing More Scrutiny Over $766 Million Task Force

search Follow ProPublica

Email Updates by email

optional

Our Hottest Stories

- The Muscular Dystrophy Patient and Olympic Medalist with the Same Genetic Disorder

- I Ramped Up My Internet Security, and You Should Too

- An Unbelievable Story of Rape

- Nursing Assistant Fired, Charged After Posting Nude Video of 93-Year-Old on Snapchat

- Afghanistan Waste Exhibit A: Kajaki Dam, More Than $300M Spent and Still Not Done

- Opting out: Inside corporate America’s push to ditch workers’ comp

- ProPublica Summer Data Institute

- How Denmark Dumped Medical Malpractice and Improved Patient Safety

- Why ProPublica Joined the Dark Web

- Mass Surveillance in America: A Timeline of Loosening Laws and Practices

An investigation released last week into why the U.S. military built a $25-million headquarters in Afghanistan that it never used condemned the behavior of one officer in particular: the top commander‘s lawyer.

In a series of emails to other officers in 2013 and 2014, Army Col. Norm Allen said that he wanted to “slow roll” investigators, that he wouldn’t personally cooperate out of loyalty to the command, and that he would consider it inappropriate for others to do so. The Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) recommended that Allen be disciplined.

Turns out not only did the Pentagon disagree, but Allen has moved up the military’s food chain. Today he is the legal advisor for the prestigious command that oversees Special Forces, such as the Navy SEALs.

The $25 Million Building in Afghanistan Nobody Needed

The U.S. military built a lavish headquarters in Afghanistan that wasn’t needed, wasn’t wanted and wasn’t ever used—at a cost to American taxpayers of at least $25 million. Read more

But his emails are drawing renewed scrutiny from both his peers in the military legal community and from U.S. senators charged with the military’s oversight.

Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, wrote in a letter to the Pentagon that “it was disturbing to read some of the comments” in Allen’s emails.

The Defense Department, McCain said, “should do everything necessary to ensure” that people comply with inspectors general, “including when it comes to investigations into the decisions made at all levels of the chain of command”–a direct rebuke to Allen’s assertions that SIGAR didn’t have the authority to look into top commanders.

Some retired and active duty judge advocates, what the military calls its lawyers, said they were appalled by how Allen had seemed to openly conspire to conceal fraud, waste and abuse–the very things that staff lawyers are supposed to keep from happening.

During the military’s own investigation into the 64,000-square-foot headquarters, Allen also appeared to coach a witness, SIGAR said. He emailed Lt. Gen. Peter Vangjel, who overruled three other generals and approved the building, and told him what investigators believed happened before getting the general’s testimony. Later, Allen emailed Vangjel to say he had appreciated his support in the past and would “try and reciprocate on this one.”

Allen declined to be interviewed for this story, but in an earlier response to SIGAR, he denied the allegations in the agency’s report that he had coached Vangjel and interfering with the investigation.

In his current job, Allen provides legal and ethical guidance to the U.S. Special Operations Command, the umbrella for all the military’s Special Forces. It has 66,000 in personnel, a more than $10-billion annual budget, and ever-increasing authority and responsibility around the world. The United States’ reliance on units such as the SEALs and the Army’s Delta Force has increased significantly since 9/11.

In light of Allen’s conduct with SIGAR, one retired lieutenant colonel and judge advocate, who has had several Iraq and Afghanistan deployments, said he could “only imagine” what kind of advice Allen is giving to a “command that spends much more than [the U.S. military in Afghanistan] and is in overall command of our Special Operations Forces.”

Calling the command the 800-pound gorilla of the military, he said that was not where you wanted a lawyer “playing fast and loose with the rules.”

Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo. and several other senators are calling for the Pentagon to hold those who advocated for the unneeded Afghanistan headquarters or obstructed its investigation accountable.

Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, said in a statement that the headquarters was a “classic example of Pentagon waste” and “actively impeding a watchdog investigation adds insult to injury.”

McCaskill called the project “one of the most outrageous, deliberate, and wasteful misuses of taxpayer dollars in Afghanistan we’ve ever seen.”

So far the Pentagon has declined to discipline anyone, deeming the building “prudent.”

In his letter, McCain wrote that he was unclear how the building “can be viewed as anything other than a failure of fiscal stewardship, let alone be described as ‘prudent.’”

The Senate Armed Services Committee will get a full briefing on the matter from the Pentagon, which will include the topic of training military lawyers to ensure they understand their ethical obligations are to the government and not to their commanders.

The headquarters controversy is likely to come up at the nomination hearing for Marine Gen. Joseph Dunford as the next chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Dunford, whom Allen worked for in Afghanistan, ordered and signed off on the military’s investigation into the headquarters. SIGAR questioned the independence and rigor of that investigation.

Related coverage: To learn more about Boondoggle HQ, please see our in-depth interactive or explore how U.S. commanders spent $2 billion in petty cash in Afghanistan in our news app, Money As a Weapons System.

Help us investigate: Involved in reconstruction efforts in Afghanistan? Share your experience with us.

Megan McCloskey

Megan McCloskey covers the military for ProPublica. Previously she was the national correspondent at Stars and Stripes.

Boondoggle HQ

The $25 Million Building in Afghanistan Nobody Needed

ProPublica, May 20, 2015

From start to finish, this 64,000-square-foot mistake could easily have been avoided. Not one, not two, but three generals tried to kill it. And they were overruled, not because they were wrong, but seemingly because no one wanted to cancel a project Congress had already given them money to build.

In the process, the story of “64K” reveals a larger truth: Once wartime spending gets rolling there’s almost no stopping it. In Afghanistan, the reconstruction effort alone has cost $109 billion, with questionable results.

The 64K project was meant for troops due to flood the country during the temporary surge in 2010. But even under the most optimistic estimates, the project wouldn’t be completed until six months after those troops would start going home.

Along the way, the state-of-the-art building, plopped in Afghanistan’s Helmand province, nearly doubled in cost and became a running joke among Marines. The Pentagon could have halted construction at many points—64K made it through five military reviews over two years—but didn’t, saying it wanted the building just in case U.S. troops ended up staying. (They didn’t.)

The Pentagon brass chalked up their decisions on the project to the inherent uncertainty of executing America’s longest war and found no wrongdoing. To them, 64K’s beginning, middle and end “was prudent.”

The $25-million price tag is a conservative number. The military also built roads and major utilities for the base at a cost of more than $20 million, some of it for 64K.

Ultimately, this story is but one chapter in a very thick book that few read. The Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction routinely documents jaw-dropping waste, but garners only fleeting attention. Just like the special inspector general for Iraq did with its own reports.

With 64K, SIGAR laid bare how this kind of waste happens and called out the players by name. The following timeline is based on the inspector general’s report, supporting documents and ProPublica interviews.

Military kept funding project despite troop withdrawal

0

$0

Here’s How the Story Unfolded:

First General Rejects 64K

Christened “Camp Leatherneck,” the base was fairly barren with dirt-floored tents for a few thousand Marines, but would grow sizably as President Barack Obama’s surge of 33,000 troops arrived in Afghanistan. The Marines were taking charge of Helmand and Nimroz provinces, an area the military called Regional Command Southwest.

They were working on creating housing, a post office, four gyms, a store and nearly 11 miles of roads—all the necessities of daily life at large bases, even in combat zones—and commanders had recently upgraded from a tent to plywood headquarters.

But in Kabul and an ocean away, at military commands in South Carolina and Florida, plans had been underway to replace the plywood with a hulking, 64,000-square-foot facility that would dwarf its surroundings in both size and sophistication. (And also suck up considerable power from a new $14-million utilities upgrade for electrical, sewage and water that planners had decided was now required on base.) Even with the growth, Mills was skeptical he needed the headquarters.

The 64K building was a part of 2010’s massive, $482-million build-up for the surge. Although Obama had made clear the flood had an end date—troops would start to withdraw in July of 2011—the military was prepping to build way past that timeframe.

In fact, despite what Obama said publicly, the military quietly assumed troop strengths would be maintained for five years and had master plans for 10, according to Army Maj. Gen. Bryan Watson, who would later be director of engineering for U.S. forces in Afghanistan.

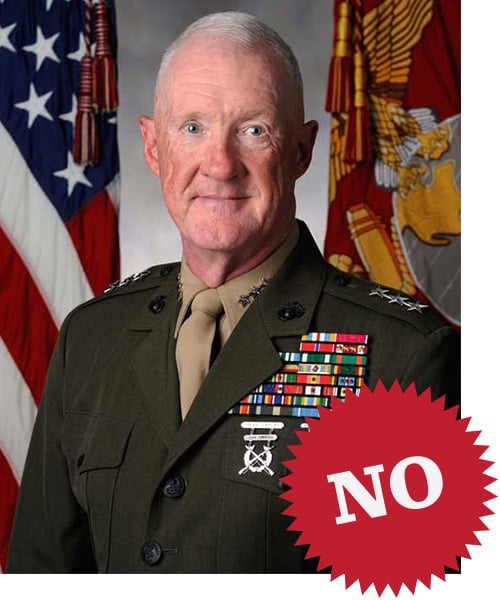

But, at least in the case of 64K, no one had asked the commander at Camp Leatherneck whether anyone needed or wanted a sprawling new facility larger than a football field. Marine Maj. Gen. Larry Nicholson, who was Mills’ predecessor, said he not only didn’t ask for it, he had no idea it was in the works.

“We certainly needed many things in those early days at Camp Leatherneck,” Nicholson would later recall, “but we were very pleased with [current headquarters], and frankly we had many far more pressing facility issues.”

That hadn’t changed when Mills took over. He reviewed all planned projects for the next two years to evaluate “the relevancy of each project to the overall counter-insurgency mission” and whether the troops needed them.

The 64K building didn’t make the cut.

Second and Third Generals Want 64K Killed

The Marines have an adequate command headquarters, he wrote in a memo, so the project is “no longer required.”

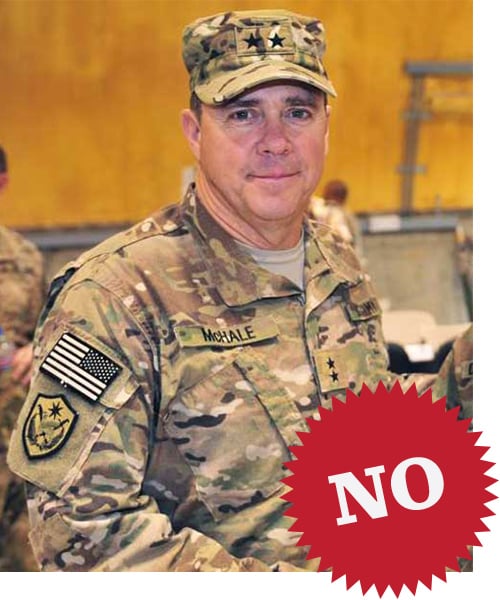

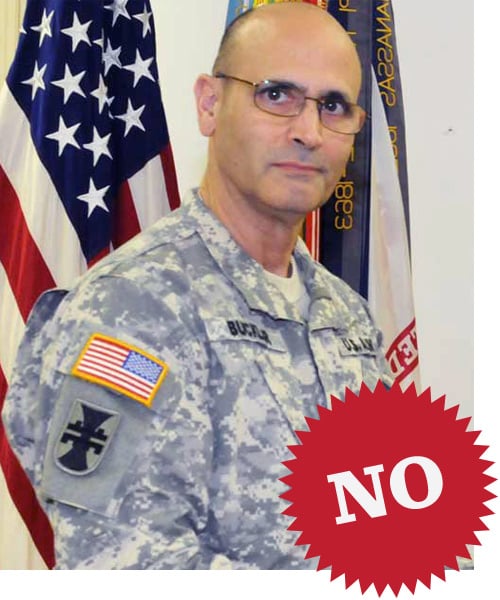

Later that week, a third general echoed Mills and McHale. Army Brig. Gen. William Buckler sent a memo to the U.S. command that oversees Afghanistan, saying that given the overall Afghanistan campaign plan and its strategy for bases, the building is “no longer required.”

Three generals had now come to the same conclusion: No one needed the 64K building. This was the time to stop the project.

Three “No” Votes Overruled By One Superior “Yes”. 64K Moves Ahead

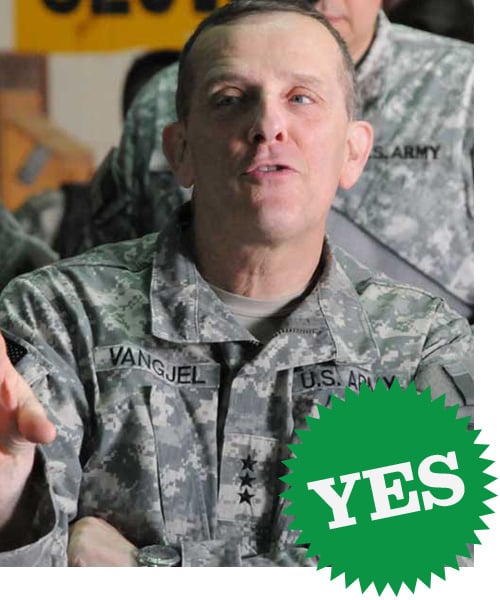

Vangjel rejected the advice of the three generals that the 64K building was superfluous. Not, SIGAR said, because he believed the building was essential, but because the money for the project was already in hand.

The previous month, funding for the surge—including $24 million specifically ticketed for the 64K building—had been signed into law. To kill the facility now and divert the funds elsewhere, the military would have to consult Congress, a bureaucratic process called “reprogramming.” And no one seemed to want that.

Vangjel agreed to Mills’ requests to cancel other Leatherneck projects that hadn’t been assigned money by Congress already, but not 64K. Cancelling the project, “which has appropriated funds, and reprogramming it for a later year is not prudent,” he wrote in a memo.

Vangjel gave no other reasons to justify spending the millions of taxpayer money.

For similar reasons, Vangjel at the same time refused to substitute the 64K building with a new request from Mills for a much smaller headquarters. Vangjel later said he was advised that a new round of approvals would delay the project too long and it might end up being too small.

But U.S. Army Central wasn’t eager to get 64K going. The command wanted to “move it to the bottom of the pile,” Vangjel’s staff member Lt. Col. Marty Norvel wrote in an email. They would like to push it “as far to the right as possible” on the calendar, as late as January 2012, and “ensure we time this award to support other operational needs.”

SIGAR found that the correspondence “confirm[ed] there was no immediate operational need for the 64K building.” Instead, “the real purpose was to retain the project for some other possible use in the future.”

Military Opens Tab

Construction Begins on 64K, Even Though No One Needs It

The Coalition forces had already begun handing control of the country back to the Afghans and would soon start pulling troops out of the country.

On June 22, Obama announced what everyone already knew. The drawdown of forces would begin in July. Ten thousand troops would be home by the end of the year, 20,000 more would leave by the end of 2012. And by the end of 2014, the combat mission would be over. Marines, in particular, would be headed out.

At this point, the 64K building wasn’t even “12 percent complete.”

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AplABHpuzqE]It was the same story throughout Afghanistan. Construction that the military decided it needed in 2009 was just starting to come to fruition. Just like everything else in government, the projects took a long time to wind through the bureaucracy. Too long for war.

So come August, the military in Afghanistan, according to Watson, was “still building like crazy.”

Tab Goes Up $109,545

Tab Goes Up $2,661

Military Axes $128 Million of Military Construction, But Not 64K

Marine Maj. Gen. John A. Toolan, the Regional Command Southwest commander at the time, canceled $128 million in military construction projects and wrote that “the time to stop building is now.”

The 64K building wasn’t on the list.

For projects already underway, Watson said, the military weighed the consequences of cancelling, including “how much was already obligated, how much could be saved after we paid the contractor termination penalties” and whether the project could be used for something else.

The Pentagon also told SIGAR that at the time 64K was required to serve as the headquarters “for an enduring presence at Camp Leatherneck.” But that conflicts with the recollections of other generals who said the matter was far from settled.

Watson wrote that at this time the military construction review for Marine bases was “very contentious because there was no clear decision on whether [Leatherneck] would become an enduring base.”

And the fate of the base would remain undecided for at least another year and a half. Marine Maj. Gen. Charles Gurganus, an RC-Southwest commander, said in an interview with ProPublica that when he left in 2013 “there were still discussions about it.”

So whether the U.S. would keep a long-term presence in Helmand was up in the air, and thousands of Marines already were going home. Yet the military continued to build a pricey, permanent headquarters facility at Leatherneck—just in case.

Tab Goes Up $105,656

Tab Goes Up $257,396

Marines’ Mission Shrinks. But 64K Still Grows

Stuck with the building, the Marines modified it to their liking. From September 2011 to April 2012, they made 15 changes. Seven increased the total cost by about $1 million. And they made an assortment of pricey upgrades, spending, for example, nearly $3 million for audio and video electronics and more than $526,000 for a video teleconference suite.

All the “bells and whistles” came from the Marines, according to Watson.

By this point, the Afghans had taken over security for all of Helmand, and the U.S. had started closing bases and sending equipment home. The Marines would soon shutter dozens of outposts.

And yet construction on 64K continued apace, seemingly without regard to the changing dynamics of the war. Stopping construction at that point would have cost more, Gurganus said. It’s a common dilemma with wartime contracts. Payments often are made up front and half the money can be spent before anything is built.

Though he said he “would have done fine with a tent,” Gurganus planned to move into 64K once the building was finished.

Finally, five months later, in October, the 64K building was done—but problems with the fire exits kept Marines from moving in right away. Then, in December, the Marines went for yet another change, this time moving around interior walls to accommodate a large conference table. The modification added more than $341,000 to the tab and caused more delays.

By the end of December, the Marines who poured into the country during the surge had gone home—and no one had used 64K.

Tab Goes Up $1,934,658

Tab Goes Up $2,774,637

Tab Goes Up $3,047,434

Tab Goes Up $88,676

Tab Goes Up $501,978

Tab Goes Up $12,480

64K Is Built. Marines Decide Not to Use It

“I have no intent to move in,” Miller wrote. “Many reasons, we are too small…we are moving into the fighting season and it is not ready.” Any further installations to the building have been halted, he continued, to “end the money drain.” (Another $19,414 went toward workers for furniture assembly regardless.)

This confirmed, SIGAR wrote in its report, “what was already known back in May 2010: that the Marines at Camp Leatherneck did not require a 64K command and control facility.”

Tab Goes Up $19,414

Empty, Fancy Building Attracts Attention of SIGAR

It was “the best constructed building I have seen in my travels to Afghanistan,” John Sopko, SIGAR’s head, told then-Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, after he saw the wood-panelled auditorium, reclining chairs for conferences and high-end credenzas during a tour.

Officers, well aware of the joke the building had become, had taken Sopko aside while he was in Afghanistan to ensure he saw it.

Sopko later learned that the military had been scrambling to determine what to do and say about what had become a white elephant.

The Pentagon told SIGAR there had already been one investigation in May and another was underway. The first investigation had concluded that the best thing to do was to convert the building to something else, maybe a gym or a movie theater, so it wasn’t a complete waste.

But Marine Gen. Joseph Dunford, who was Commander of U.S. Forces-Afghanistan and who would later be nominated as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, realized those conclusions were insufficient. The building, he wrote in his order for a new investigation, “has the potential to draw significant attention from auditors and Congress, and raises questions as to its approval and construction.” He had this new investigation helmed by a two-star general.

In August, a month after SIGAR began asking questions, Army Maj. Gen. James Richardson concluded no one was at fault in the construction of the building.

Vangjel was correct in refusing the Marines’ request to cancel the project because he knew that 64K was part of a larger “strategic vision” for long-term use of Camp Leatherneck, Richardson wrote in his report. The Marines’ request for a smaller headquarters also proved that there was a need for some sort of facility.

An email exchange from Richardson’s investigation starkly displayed the pervasive military culture of nonchalance towards costs. Although “as a taxpayer [I’m] not happy with waste,” Navy Cmdr. Timothy Wallace wrote Richardson, given how much the military has spent on construction in the uncertain environment of Afghanistan, “if $30 million is the worst of it, that’s probably not bad in the grand scheme of things.”

In his final report Richardson also heaped blame on the Marines who did not attempt to “reduce or prevent costs” until three years after the cancellation request.

To bolster his finding that the building was appropriately constructed, he noted that it had progressed through the leadership of five different Marine commanders. He did not mention that three out of five had never been consulted or had deemed the project unnecessary. The first didn’t know about it, the second tried to cancel it, and the fifth arrived after it was done and said he wasn’t going to move in.

Richardson recommended that 64K be completely finished by adding the required communication equipment and that troops be ordered to use it as their headquarters.

This recommendation, or “viable option” as Richardson put it, would cost an additional $5 million—more than twice the cost of just demolishing it.

SIGAR Doubts Pentagon, Opens Own Investigation

“We were surprised that the results we saw didn’t really make much sense,” Sopko said.

The military was not pleased and immediately moved to quash, or at least inhibit, SIGAR’s work.

Col. Norman Allen, a staff lawyer for Dunford at the U.S. Forces-Afghanistan command, sent an email to some command staff saying he’d prefer that they “slow-roll” SIGAR, but thought they couldn’t.

In February, Allen sent another email mentioning “loyalty to the command” and noting that he “would consider it inappropriate” for people to tell “SIGAR what they think of the…investigation appointed and approved by the commander.”

Allen also wrote that he, personally, has a good deal of knowledge about the investigation, but he wasn’t going to cooperate with SIGAR.

Three days later, the U.S. Forces-Afghanistan inspector general—who was on those email chains—sent a memo asking that “appropriate authorities intervene to cease SIGAR’s evaluation of command internal business.” How the military conducted its investigation of the 64K building, he wrote, is out of SIGAR’s jurisdiction.

As SIGAR discovered those documents, investigators were troubled, because as Dunford’s legal advisor, Allen was in a position to discourage full cooperation.

SIGAR’s Sopko said in an interview that he couldn’t fathom how anyone would think that as an independent inspector general he couldn’t look behind the scenes.

“That’s like saying I can look at fraud, waste and abuse but I can’t look at generals. Or I can look at fraud, waste and abuse, but not the reasons why” they occur, he said.

The Pentagon stalled Sopko where it could, initially withholding from SIGAR the exhibits for the second investigation done by Richardson, for example. Then officers resisted turning over any other documents related to 64K, and Allen commented in an email that he didn’t think Sopko “had the authority” to force them to, and, regardless, “[we] don’t think we’re working on providing him more info.” Forced by law to reply, some unclassified documents were turned over on a classified disc, requiring time-consuming procedures and limiting who could view them.

“I think they delayed this a long time,” Sopko said.

Later in the year, during a summer visit to Camp Leatherneck as SIGAR’s investigation was ongoing, Sopko said he learned his military escorts had been told not to even drive by the 64K building with him.

Marines Go Home Without Ever Using 64K

Employing serious understatement, one Defense Department document stated: “certain technologies, such as those designed in the [64K building] are not as accessible to nations in this region, whether because of cost or lack of interest or requirement.”

The document said there was “no knowledge” that Afghanistan has the “basic desire to maintain and operate” the building.

Military Bungled 64K; Training Needed In Not Wasting Taxpayer Money

SIGAR’s final report blasted the military for almost every decision it made in the 64K boondoggle. The military, it charged, disregarded sound advice from three generals for seemingly no valid reason. It attempted to frustrate SIGAR’s examination. And it performed a limited, ineffectual investigation of the project.

SIGAR said that 64K cost the taxpayers $36 million. But its math both fails to include some costs and sweeps in too much of others. Investigators didn’t account for the $1 million worth of modifications and the $8.3 million worth of communications equipment installed in the building, but added in the full cost of the utilities infrastructure and the nearly 11 miles of roads — even though they were for the entire base that housed about 20,000 people at its peak.

The Pentagon does not consider the utilities and the roads part of the building’s cost, only conceding that the building, with the modifications and communication equipment, cost $25 million.

ProPublica used the $25-million figure and did not count the utilities and roads cost even though a portion of each was for 64K. Parsing the cost wasn’t possible.

SIGAR found that Richardson “mismanaged” the inquiry, failed “to carry out a fulsome investigation,” and had “no reasonable basis” to recommend that the military complete and move into the 64K building at considerable additional cost.

“Not only was the surge long over,” the report said, “but the U.S. had already begun to withdraw troops from Afghanistan and Camp Leatherneck’s future was in doubt.”

One startling discovery: Richardson never spoke to Vangjel, the man who denied the request to kill 64K. Richardson also didn’t conduct any interviews or take sworn statements from other witnesses, instead posing questions over email, SIGAR’s report said.

In an interview, Sopko said Richardson’s explanation—that he didn’t need to speak to Vangjel because he had sufficient information from documentation—“makes no sense, and particularly not from a general” who should know better.

SIGAR, however, did interview Vangjel and wasn’t satisfied with his answers. He told them his decision to deny the cancellation was based on a “larger strategic plan” for Camp Leatherneck.

“However, [Vangjel] was unable to point to any documents, classified or unclassified, showing the existence of such a strategic plan,” SIGAR wrote.

Further, SIGAR cited concerns that Allen had, in essence, coached Vangjel on how to respond by emailing him advanced excerpts of the military’s own investigation’s findings.

Allen sent Vangjel an email including language from the report that said Vangjel’s decision was based on the “strategic vision of the enduring presence” in Helmand.

“Rather than simply asking General Vangjel why he thought it was prudent to approve the 64K building, Col. Allen appears to have provided him with the answer,” SIGAR wrote.

Mills, the general who asked to cancel 64K and had since been promoted to lieutenant general, wrote Allen that he didn’t recall being consulted about the denial—contradicting both Vangjel’s claims and the military’s report. If Vangjel had talked to Marines before his decision, Mills said, he did so “well below Flag Officer level.”

Both Allen and Vangjel disputed SIGAR’s characterization and conclusions. They each responded in writing: “I never sought to interfere with legal requirements or to coach the testimony of witnesses” and there was “no basis to question my integrity,” Allen said.

Vangjel said he thought there were “significant errors throughout [SIGAR’s] report and inadequate consideration of context and timing.” He also denied being “coached” by Allen and repeated his assertions that there was both a need at the time for 64K and a long-term requirement.

Richardson, who is now in charge of aviation and missile readiness for the Army, didn’t provide SIGAR with any comments on its report.

In its report, SIGAR recommended that Vangjel, Richardson and Allen be disciplined, and that the Pentagon do training, basically, on how not to waste taxpayer money.

The Pentagon rejected those recommendations, saying the military already has enough rules to prevent financial waste and maintaining that the decision to build the 64K building “was prudent.”

The one recommendation that SIGAR and the Pentagon agreed on is a need to instruct service members on their legal obligation to cooperate with inspectors general.

But no one was disciplined. In fact, by November 2011, Vangjel had been promoted to lieutenant general and taken over a new post: He was the Army’s inspector general in charge of sniffing out fraud, waste and abuse. He retired in February.

Today, the lavish project serves as the headquarters of a small Afghan regiment, according to an Afghan colonel who is a spokesman with the Ministry of Defense. Unable to make use of the high-tech “bells and whistles,” it brought its own generator and occupies only a fraction of a cavernous space meant for at least 1,200 people.

SOURCES

Additional Design & Development: Mike Tigas, ProPublica. Data: ProPublica interviews; reports and supporting documents from the the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction and the United States Marine Corps.