Is Facebook’s Facial-Scanning Technology Invading Your Privacy Rights?

Facebook Inc.’s software knows your face almost as well as your mother does. And like mom, it isn’t asking your permission to do what it wants with old photos.

While millions of internet users embrace the tagging of family and friends in photos, others worried there’s something devious afoot are trying block Facebook as well as Google from amassing such data.

As advances in facial recognition technology give companies the potential to profit from biometric data, privacy advocates see a pattern in how the world’s largest social network and search engine have sold users’ viewing histories for advertising. The companies insist that gathering data on what you look like isn’t against the law, even without your permission.

If judges agree with Facebook and Google, they may be able to kill off lawsuits filed under a unique Illinois law that carries fines of $1,000 to $5,000 each time a person’s image is used without permission — big enough for a liability headache if claims on behalf of millions of consumers proceed as class actions. A loss by the companies could lead to new restrictions on using biometrics in the U.S., similar to those in Europe and Canada.

Facebook declined to comment on its court fight. Google hasn’t responded to requests for comment.

Courts have struggled over what qualifies as an injury to pursue a privacy case in lawsuits accusing Facebook and Google of siphoning users’ personal information from e-mails and monitoring their web browsing habits. Suits over selling the data to advertisers have often failed.

This year, the U.S. Supreme Court set a “concrete injury” standard for privacy suits, a ruling that both sides are using to argue their case ahead of a hearing Thursday in San Francisco over Facebook’s bid to dismiss the biometrics case.

Google is fending off suits in Chicago, arguing that the Illinois statute can’t apply outside the state under the Constitution’s interstate commerce rules. Google also contends the Illinois law doesn’t regulate photos.

For more on the Illinois biometrics law, click here.

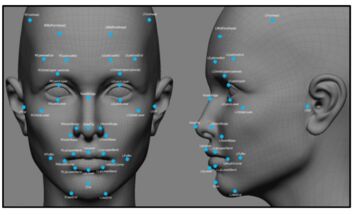

Facebook encourages users to “tag” people in photographs they upload in their personal posts and the social network stores the collected information. The company uses a program it calls DeepFace to match other photos of a person. Alphabet Inc.’s cloud-based Google Photos service uses similar technology.

The billions of images Facebook is thought to be collecting could be even more valuable to identity thieves than the names, addresses, and credit card numbers now targeted by hackers, according to privacy advocates and legal experts.

While those types of information are mutable — even Social Security numbers can be changed — biometric data for retinas, fingerprints, hands, face geometry and blood samples, are unique identifiers.

“Biometric identifiers are a key way to link together information about people,” such as discrete financial, medical and educational records, said Marc Rotenberg, the president of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, who isn’t involved in the case. Facebook has “cleverly got its users to improve the accuracy of its own database,” he said.

And just how good is Facebook’s technology? According to the company’s research, DeepFace recognizes faces with an accuracy rate of 97.35 percent compared with 97.5 percent for humans — including mothers.

Rotenberg said the privacy concerns are twofold: Facebook might sell the information to retailers or be forced to turn it over to law enforcement — in both cases without users knowing it.

While most of the earlier privacy lawsuits relied on federal wiretap laws, the facial recognition cases hinge on the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act.

The Illinois residents who sued under the 2008 law say it gives them a “property interest” in the algorithms that constitute their digital identities — in other words, that gives them grounds to accuse Facebook of real harm. Facebook got the case moved to San Francisco.

“Just as trade secrets or subscriber lists can be proprietary to a company like Facebook, unique and unchangeable biometric identifiers are proprietary to individuals,” according to their complaint. They also claim an “informational injury” because Facebook didn’t get consent to collect their so-called faceprints.

Facebook says the lawsuit should be thrown out because the users haven’t suffered a concrete injury such as physical harm, loss of money or property; or even a denial of their right to free speech or religion.

The plaintiffs “have offered no specific or coherent allegations explaining how this collection and storage actually affects their privacy — much less causes them concrete harm,” Facebook argued in a court filing.

Facebook offered examples that might work, such as if users were identified in an embarrassing photo that cost them their jobs, were victims of identity theft, or were caught in a compromising situation that harmed their relationships.

While one person might be able to bring such a case, a group lawsuit would be impossible because it would “create a sea of individualized issues,” Facebook says.

Legal experts say it’s unclear which side will benefit from the Supreme Court’s “concrete harm” ruling in a case involving search engine operator Spokeo Inc.

“Spokeo is vague about what kinds of injury are concrete enough to count,” said Julie Cohen, a professor at Georgetown University Law Center. “Everybody is scrambling for advantage.”

Facebook v. Privacy Law

December 2005 — Facebook introduces photo tagging

October 2008 — Illinois adopts Biometric Information Privacy Act

June 2012 — Facebook acquires Israeli facial recognition developer Face.com

September 2012 — Facebook ceases facial recognition in Europe

2015-2016 — Facebook, Google, Shutterfly and Snapchat sued under Illinois biometrics law. Shutterfly settles confidentially.

May 2016 — Illinois lawmaker proposes excluding photos from biometrics law, then shelves bill after privacy advocates complain

October 2016 — Facebook makes second attempt to get biometrics lawsuit thrown out

The Facebook case is In re Facebook Biometric Information Privacy Litigation, 15-cv-03747, U.S. District Court, Northern District of California (San Francisco). The Google cases are Rivera v. Google, 16-cv-02714, and Weiss v. Google, 16-cv-02870, U.S. District Court, Northern District of Illinois (Chicago).